As challenge to MTA deal awaits a judge, did Forest City Ratner really have the MTA over a barrel, or was it the other way around?

All the legal papers have been filed in the case challenging the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's revision of the Vanderbilt Yard deal with Forest City Ratner. As we await a decision by the judge--no oral argument is expected, and a decision could take weeks--two things must be kept in mind.

First, as the MTA reminds state Supreme Court Justice Michael Stallman, the standards of review in such an Article 78 proceeding is "highly deferential to agency action."

So, no matter the facts, it's an uphill climb for the plaintiffs, AY opponent Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, joined by four elected officials and the Straphangers Campaign, in charging that a state law (the Public Authorities Accountability Act, or PAAA) passed in 2005 requires an independent appraisal of the property and that a seller seek out competitive offers.

If successful, the lawsuit (which also names Forest City Ratner as a defendant) could force the MTA to seek a new bid for the railyard. But the lawsuit is not seen by state officials as stopping either the bond sale or the pursuit of eminent domain.

MTA fortunate in deal "evolution"?

Second, the MTA's posture in the case is quite questionable, especially at a time when the agency is cash-poor, with revenue projections $200 million behind schedule.

Though the MTA agreed to a revised deal with less money upfront ($20 million, rather than $100 million), a smaller and less valuable railyard, and a temporary yard that would linger longer (up to 80 months, rather than 32 months as originally anticipated), it considers itself lucky.

As MTA Chief Financial Officer Gary Dellaverson asserted in an affidavit, "It is remarkable that MTA was able to negotiate a revised proposal that, despite those changed economic circumstances, maintained the main elements of consideration first obtained--albeit in somewhat revised form."

Instead of $100 million in hand, the MTA could get the $80 million over 22 years, at a generous 6.5% interest rate unavailable to others seeking real estate financing. Forest City would provide a railyard worth $150 million. (It was originally to cost $182 million, then rose to $250 million before "value engineering.")

However, if the developer walks away, it would forfeit only an $86 million letter of credit to allow the MTA to build a presumably less expensive railyard. (The MTA, however, would also be able to re-sell development rights.)

Yes, the MTA would still get a new subway entrance and new tax revenue.

But the language of the defendants is curious. The MTA in legal papers calls the package merely “an evolution in the terms of the deal.” FCR deems the changes “insubstantial modifications to the business terms.”

Who's over a barrel?

In the MTA's eyes, Forest City Ratner had the agency over a barrel. That's why the MTA didn't get a new appraisal of the railyard, figuring a new valuation—due to the decline in real estate values and the increased cost of building a platform--would inevitably be less than in 2005, exposing it to a worse deal.

But maybe it was the other way around. Didn't the MTA have Forest City over a barrel?

The developer--well, its principal and its parent--has a major stake in the money-losing Nets basketball team that it wants desperately to move. The developer faces a December 31, 2009 deadline to get tax-exempt bonds issued for the Atlantic Yards arena. In April, in fact, a FCR executive privately confessed to being "a freaked out developer with an arena that must start this year."

As the suit noted, Dellaverson acknowledged that the transaction had to be approved quickly--the board had 48 hours--because, as he said at a June 22 MTA Finance Committee meeting, "it really relates to Forest City's desire to market their bonds as a tax-exempt issuance [by a December 31 deadline]."

So an appraisal--at least one accompanied by some longitudinal sense of the real estate market--might have suggested that the value would rebound and the MTA board might have considered the value of seeking a new offer or waiting for a new one. As the New York Times editorialized in a somewhat similar case in 1994:

Except, from the perspective of the MTA, it was apparently impossible to walk away. Despite a lack of final contracts, the train had left the station. Forest City Ratner had begun significant work on the Vanderbilt Yard under a license agreement. The city and state had contributed well over $200 million in subsidies, part of a $305 million direct allotment. And FCR had bought most but not all of the land needed for the project.

The MTA said that a new appraisal would not only have "seriously jeopardized" its efforts to maximize its return regarding the disposition of Vanderbilt Yard property rights, but also the costs associated with track relocation and platform construction.

But the latter is because FCR was already working on it.

As Forest City said in legal papers, "ESDC and FCRC already have achieved substantial progress in implementing the Project, and the public would not be served by opening the Project to new bidding."

Well, the benefits of the project as it stands are certainly open to question, as the suit charges--and the MTA does not solidly refute, as described below.

But the key is that the political establishment behind the MTA board--Mayor Mike Bloomberg and Governor David Paterson--wanted the deal to happen, just as Bloomberg and then-Gov. George Pataki wanted the deal to happen in 2005. (Or maybe Paterson, distracted by budget issues, is more agnostic but acceded to Bloomberg’s desire and the inertial pull of the ESDC.)

And Forest City is no stranger to hardball, renegotiating the Beekman Tower construction agreement in midstream and even choosing to delay a mortgage payment on land in the AY footprint.

Impact on bond sale?

Writing October 13, I wondered if the suit could throw a wrench into Forest City Ratner's plan have the state sell tax-exempt bonds and for arena construction to begin this year.

However, according to the Barclays Center Arena Preliminary Official Statement (8.2 MB PDF), FCR “believes that the MTA complied with all applicable legal requirements and expects that the [defendants] will prevail in this proceeding.”

Fuzzy numbers

It’s a bit hard to sort out the value of Forest City Ratner’s railyard bid, or the comparison of that bid with the one made by rival Extell.

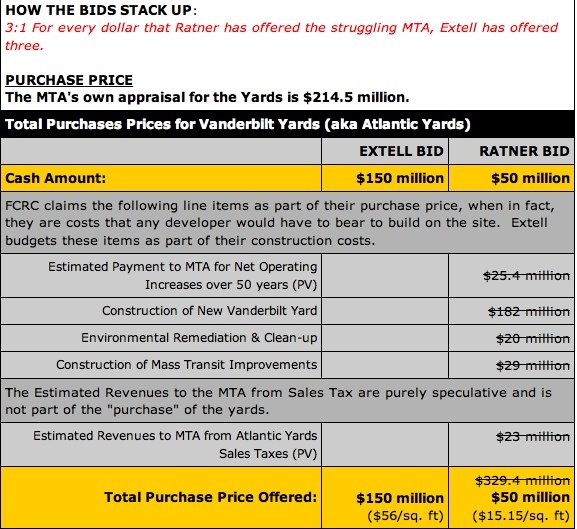

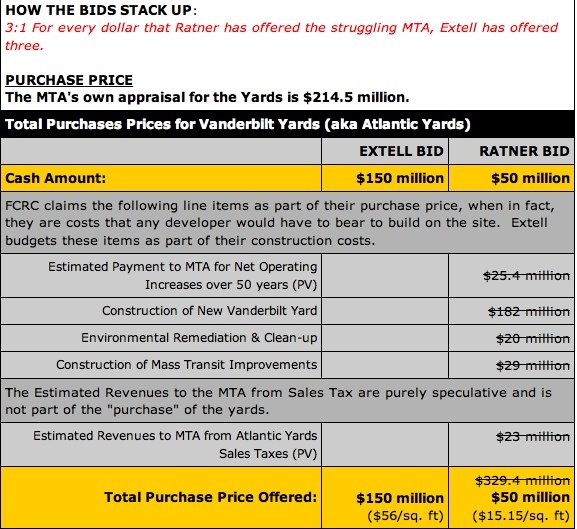

According to the MTA and FCR, the latter’s bid--initially $50 million cash, then $100 million after renegotiation--was by far more attractive as a package. Atlantic Yards opponents and critics have steadily argued Extell’s bid, which offered $150 million in cash, was far superior.

It's complicated.

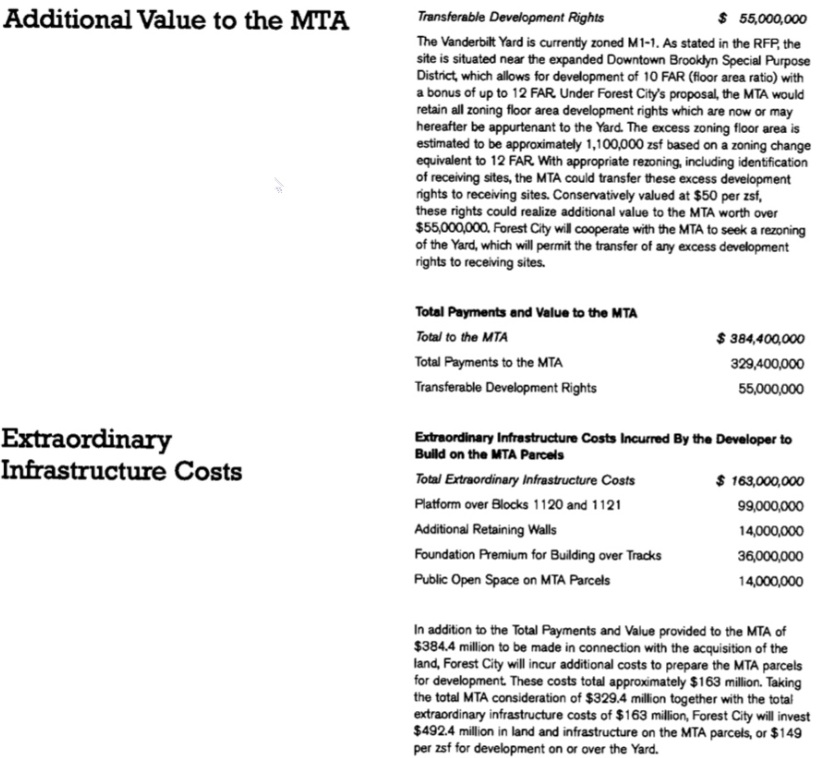

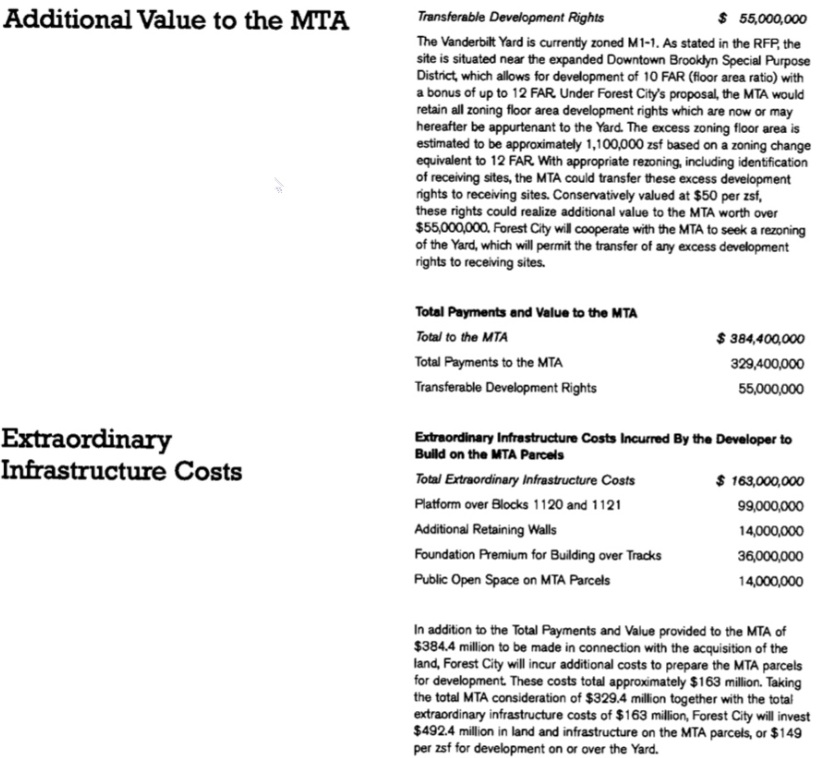

The 8.5-acre Vanderbilt Yard is the crucial piece of publicly owned land within the 22-acre footprint proposed for Atlantic Yards. In 2005, Forest City Ratner, which had been essentially anointed the project in December 2003, bid $50 million cash, part of a package it now says was worth $329.4 million. (Actually, the developer originally claimed that bid was worth $492.4 million, including $163 million in "extraordinary infrastructure costs” to build over the railyard. Click on graphic at right to enlarge.)

The 8.5-acre Vanderbilt Yard is the crucial piece of publicly owned land within the 22-acre footprint proposed for Atlantic Yards. In 2005, Forest City Ratner, which had been essentially anointed the project in December 2003, bid $50 million cash, part of a package it now says was worth $329.4 million. (Actually, the developer originally claimed that bid was worth $492.4 million, including $163 million in "extraordinary infrastructure costs” to build over the railyard. Click on graphic at right to enlarge.)

After rival Extell—the only developer to respond to DDDB’s circulation of the RFP—bid $150 million, the MTA board chose instead to negotiate exclusively with Forest City. Legal papers in the case suggest that the MTA saw it as leverage to get FCR to up its bid.

However, the MTA's appraiser said the railyard was worth $214.5 million to a bidder who also included a replacement railyard. The total value was $271.2 million.

That suggests the replacement railyard would cost only $56.7 million, a number disparaged in the MTA's legal papers. Forest City Ratner's replacement railyard would cost much more, and Extell's would have cost more, but not as much as FCR's plan.

The difference: Extell, not building an arena, would not have had to build a temporary yard.

The Extell bid

While the lawsuit charged that Dellaverson did not explain why MTA did not get a new appraisal or solicit a new proposal from Extell, in its legal answer, the MTA said there was no request for any explanation as to why the MTA had not contacted Extell or sought an appraisal, nor was there a reason Extell would be interested in submitting a new proposal.

Extell head Gary Barnett in a December 2007 interview with the Observer said, "We are shocked—shocked—that we bid $150 million, [Forest City Chairman Bruce] Ratner bid $50 million, yet he somehow managed to get it."

But Barnett also said "we know when we're beat."

The petitioners responded to the MTA:

Let's take a look at the comparison chart produced by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn. DDDB says that Extell would have provided everything that Forest City Ratner would have.

Let's take a look at the comparison chart produced by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn. DDDB says that Extell would have provided everything that Forest City Ratner would have.

I don't believe that's accurate; nor do I believe that the MTA's portrayal is fair, either.

MTA notes in legal papers that Extell had said it would "in all likelihood" receive up to $150 million in subsidy but did not indicate it had begun to negotiate with the city or state as FCR had.

In other words, Forest City Ratner had already locked in the subsidies. Indeed, a 2005 letter to the MTA from Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff indicated that the city would not offer similar subsidies to another plan.

Nor, said the MTA, did Extell offer indemnification for environmental risks and did not offer to pay MTA expenses in relocating the Vanderbilt Yard.

But the dismissal of the Extell bid leaves out a few things. (These are not all mentioned in the lawsuit.) FCR said it could address environmental risks by using Brownfield Tax Credits—presumably available to any developer. Extell, as noted, didn't have to build a temporary yard.

And it was never asked to develop its bid. In a cover letter, Extell's Barnett wrote, "We believe our proposal could have been even more detailed and responsive had the MTA offered a longer period for response to its RFP, either initially or in response to our formal written request for an extension. We regret that you declined our request."

Unlike FCR, Extell was not planning to build a new subway entrance--originally to cost $29 million, now $50 million--nor build a project that would add as large amount of new sales taxes. On the other hand, Extell wasn't asking for $305 million in direct subsidies from the city and state nor the gift of arena naming rights.

Bottom line

The bottom line is that no one ever did a full cost-benefit analysis for all the public parties on the Forest City Ratner deal or the Extell deal.

Another reasons for fuzziness

The petitioners pointed out another inconsistency:

Public benefits

While the MTA claimed it did not need to follow a public bidding process, because the sale was allowed by the PAAA as furthering the public interest, there's no evidence, the suit charges, that the MTA conducted "any actual analysis of the public benefits to be gained by the sale of the Vanderbilt Yard to FCR," nor did it acknowledge the "diminishment of the Project’s anticipated public benefits."

The MTA and the FCR denied that.

The petition charged that, the MTA Board’s June 24, 2009 resolution merely recited, in rote fashion, the same “significant public uses and purpose” of the Project that it had recited in 2005, such as “the construction of thousands of rental housing units for low-, moderate- and middle-income New Yorkers”, “the erection of commercial office space to promote future economic growth and new jobs”, even though all or substantial portions of all of those benefits had already been either eliminated from the Project or put on indefinite hold.

The MTA and FCR denied that and referred the court to the resolution. However, while it offers other justifications for the deal, it does not acknowledge the doubts about the promised benefits.

DDDB's bid

The suit charges that the fair market value of the property was never discussed. It also charges that the MTA did not ask Extell for a competing proposal nor did it entertain DDDB's announced bid, at the June 24 meeting, of $120 million.

In an affidavit, former MTA board chair Dale Hemmerdinger called DDDB offer a political stunt rather than a bona fide responsive offer.

Also, the MTA said the UNITY Plan developed by DDDB failed to demonstrated the proposers' financial qualifications, no proven ability to obtain financing for projects of similar size. And it noted that the ESDC had previously rejected UNITY plan during its review of the project.

The petitioners responded:

Did the MTA really analyze public benefits of the deal? In his affidavit, Hemmerdinger stated:

(The IBO's formal report came out after the MTA vote, but an IBO rep had testified to this effect at a state Senate oversight hearing in May.)

The MTA focused on construction jobs:

FCR came up with different numbers:

So why would a smaller railyard be OK? Because, said the MTA, its plans have changed:

In his affidavit, Dellaverson further explained a reason to stick with the deal:

Legal opinion obtained?

Did the MTA obtain a opinion from legal counsel advising it that its disposition of the Vanderbilt Yard was lawful? (I wrote that the MTA got a checkoff, at least.) In its answer, the MTA punted:

Both Forest City Ratner said the MTA complied with the PAAA because it had in the record the previous appraisal, from 2005.

Moreover, said FCR, the MTA board was not obligated to comply with the law, because a preliminary determination to dispose of the Vanderbilt Yard properties and development rights to FCR was made in 2005, before the effective date of the PAAA, and affirmed in 2006, with only “modifications to the business terms” approved in 2009.

The MTA, more cautiously, said “it arguably does not even apply.”

In an reply brief, the plaintiffs responded:

Deal "evolution"?

Was the 2009 transaction part of a sequence? The plaintiffs disagree:

(Actually, the letter—at the end of the Helena Williams affidavit—says that transaction “may fall within the purview” of the PAAA.)

The issue of standing

The defendants say that the petitioners shouldn't even be in court.

The petitioners argued that DDDB, as a potential bidder, has been directly injured, and that it has organizational standing, given that the interests at issue "are sufficiently germane to the association's purposes that it is an appropriate representative of those interests."

So too the Straphangers has associational standing, given its interest in MTA operations, as do the elected officials represent districts encompassing or near the Vanderbilt Yard.

The suit said those officials--State Senator Velmanette Montgomery, Assemblymember Jim Brennan, Assemblymember Joan Millman--voted to pass the PAAA, "and are interested in ensuring that their votes are not rendered meaningless by MTA’s violation of the PAAA." (Also a plaintiff is City Council Member Letitia James.)

The MTA (as did FCR), however, responded none of the petitioners have standing, since the only injured party is another legitimate bidder--e.g., Extell--and DDDB wasn’t such a legitimate bidder.

The question of standing is one the petitioners hope the court will construe broadly, because “no party other than petitioners is in a position to challenge MTA’s unlawful action.”

First, as the MTA reminds state Supreme Court Justice Michael Stallman, the standards of review in such an Article 78 proceeding is "highly deferential to agency action."

So, no matter the facts, it's an uphill climb for the plaintiffs, AY opponent Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, joined by four elected officials and the Straphangers Campaign, in charging that a state law (the Public Authorities Accountability Act, or PAAA) passed in 2005 requires an independent appraisal of the property and that a seller seek out competitive offers.

If successful, the lawsuit (which also names Forest City Ratner as a defendant) could force the MTA to seek a new bid for the railyard. But the lawsuit is not seen by state officials as stopping either the bond sale or the pursuit of eminent domain.

MTA fortunate in deal "evolution"?

Second, the MTA's posture in the case is quite questionable, especially at a time when the agency is cash-poor, with revenue projections $200 million behind schedule.

Though the MTA agreed to a revised deal with less money upfront ($20 million, rather than $100 million), a smaller and less valuable railyard, and a temporary yard that would linger longer (up to 80 months, rather than 32 months as originally anticipated), it considers itself lucky.

As MTA Chief Financial Officer Gary Dellaverson asserted in an affidavit, "It is remarkable that MTA was able to negotiate a revised proposal that, despite those changed economic circumstances, maintained the main elements of consideration first obtained--albeit in somewhat revised form."

Instead of $100 million in hand, the MTA could get the $80 million over 22 years, at a generous 6.5% interest rate unavailable to others seeking real estate financing. Forest City would provide a railyard worth $150 million. (It was originally to cost $182 million, then rose to $250 million before "value engineering.")

However, if the developer walks away, it would forfeit only an $86 million letter of credit to allow the MTA to build a presumably less expensive railyard. (The MTA, however, would also be able to re-sell development rights.)

Yes, the MTA would still get a new subway entrance and new tax revenue.

But the language of the defendants is curious. The MTA in legal papers calls the package merely “an evolution in the terms of the deal.” FCR deems the changes “insubstantial modifications to the business terms.”

Who's over a barrel?

In the MTA's eyes, Forest City Ratner had the agency over a barrel. That's why the MTA didn't get a new appraisal of the railyard, figuring a new valuation—due to the decline in real estate values and the increased cost of building a platform--would inevitably be less than in 2005, exposing it to a worse deal.

But maybe it was the other way around. Didn't the MTA have Forest City over a barrel?

The developer--well, its principal and its parent--has a major stake in the money-losing Nets basketball team that it wants desperately to move. The developer faces a December 31, 2009 deadline to get tax-exempt bonds issued for the Atlantic Yards arena. In April, in fact, a FCR executive privately confessed to being "a freaked out developer with an arena that must start this year."

As the suit noted, Dellaverson acknowledged that the transaction had to be approved quickly--the board had 48 hours--because, as he said at a June 22 MTA Finance Committee meeting, "it really relates to Forest City's desire to market their bonds as a tax-exempt issuance [by a December 31 deadline]."

So an appraisal--at least one accompanied by some longitudinal sense of the real estate market--might have suggested that the value would rebound and the MTA board might have considered the value of seeking a new offer or waiting for a new one. As the New York Times editorialized in a somewhat similar case in 1994:

A rebounding economy will likely increase its value. It is wiser to walk away than stumble into a giveaway."Too big to fail

Except, from the perspective of the MTA, it was apparently impossible to walk away. Despite a lack of final contracts, the train had left the station. Forest City Ratner had begun significant work on the Vanderbilt Yard under a license agreement. The city and state had contributed well over $200 million in subsidies, part of a $305 million direct allotment. And FCR had bought most but not all of the land needed for the project.

The MTA said that a new appraisal would not only have "seriously jeopardized" its efforts to maximize its return regarding the disposition of Vanderbilt Yard property rights, but also the costs associated with track relocation and platform construction.

But the latter is because FCR was already working on it.

As Forest City said in legal papers, "ESDC and FCRC already have achieved substantial progress in implementing the Project, and the public would not be served by opening the Project to new bidding."

Well, the benefits of the project as it stands are certainly open to question, as the suit charges--and the MTA does not solidly refute, as described below.

But the key is that the political establishment behind the MTA board--Mayor Mike Bloomberg and Governor David Paterson--wanted the deal to happen, just as Bloomberg and then-Gov. George Pataki wanted the deal to happen in 2005. (Or maybe Paterson, distracted by budget issues, is more agnostic but acceded to Bloomberg’s desire and the inertial pull of the ESDC.)

And Forest City is no stranger to hardball, renegotiating the Beekman Tower construction agreement in midstream and even choosing to delay a mortgage payment on land in the AY footprint.

Impact on bond sale?

Writing October 13, I wondered if the suit could throw a wrench into Forest City Ratner's plan have the state sell tax-exempt bonds and for arena construction to begin this year.

However, according to the Barclays Center Arena Preliminary Official Statement (8.2 MB PDF), FCR “believes that the MTA complied with all applicable legal requirements and expects that the [defendants] will prevail in this proceeding.”

Fuzzy numbers

It’s a bit hard to sort out the value of Forest City Ratner’s railyard bid, or the comparison of that bid with the one made by rival Extell.

According to the MTA and FCR, the latter’s bid--initially $50 million cash, then $100 million after renegotiation--was by far more attractive as a package. Atlantic Yards opponents and critics have steadily argued Extell’s bid, which offered $150 million in cash, was far superior.

It's complicated.

The 8.5-acre Vanderbilt Yard is the crucial piece of publicly owned land within the 22-acre footprint proposed for Atlantic Yards. In 2005, Forest City Ratner, which had been essentially anointed the project in December 2003, bid $50 million cash, part of a package it now says was worth $329.4 million. (Actually, the developer originally claimed that bid was worth $492.4 million, including $163 million in "extraordinary infrastructure costs” to build over the railyard. Click on graphic at right to enlarge.)

The 8.5-acre Vanderbilt Yard is the crucial piece of publicly owned land within the 22-acre footprint proposed for Atlantic Yards. In 2005, Forest City Ratner, which had been essentially anointed the project in December 2003, bid $50 million cash, part of a package it now says was worth $329.4 million. (Actually, the developer originally claimed that bid was worth $492.4 million, including $163 million in "extraordinary infrastructure costs” to build over the railyard. Click on graphic at right to enlarge.)After rival Extell—the only developer to respond to DDDB’s circulation of the RFP—bid $150 million, the MTA board chose instead to negotiate exclusively with Forest City. Legal papers in the case suggest that the MTA saw it as leverage to get FCR to up its bid.

However, the MTA's appraiser said the railyard was worth $214.5 million to a bidder who also included a replacement railyard. The total value was $271.2 million.

That suggests the replacement railyard would cost only $56.7 million, a number disparaged in the MTA's legal papers. Forest City Ratner's replacement railyard would cost much more, and Extell's would have cost more, but not as much as FCR's plan.

The difference: Extell, not building an arena, would not have had to build a temporary yard.

The Extell bid

While the lawsuit charged that Dellaverson did not explain why MTA did not get a new appraisal or solicit a new proposal from Extell, in its legal answer, the MTA said there was no request for any explanation as to why the MTA had not contacted Extell or sought an appraisal, nor was there a reason Extell would be interested in submitting a new proposal.

Extell head Gary Barnett in a December 2007 interview with the Observer said, "We are shocked—shocked—that we bid $150 million, [Forest City Chairman Bruce] Ratner bid $50 million, yet he somehow managed to get it."

But Barnett also said "we know when we're beat."

The petitioners responded to the MTA:

Thus, according to Dellaverson, because Extell, which in 2005 expended time and resources to put together a detailed, viable development proposal on 43 days’ notice only to have MTA use its proposal as a stalking horse to improve FCR’s offer, did not come knocking on MTA’s door in 2009, MTA was entitled to assume Extell would not be responsive to a genuine expression of interest from MTA, and, therefore, MTA could simply disregard the express requirements of the PAAA.Comparison chart

Dellaverson’s argument is both cynical and absurd. Extell, as a private, for-profit developer, presumably is motivated to expend its time and resources pursuing development projects that might actually happen. Given MTA’s failure to solicit any proposals at all in 2009 other than from FCR, its prior refusal to work with Extell on its proposal in 2005, and its clear, repeatedly stated preference for FCR since before 2005 up through 2009, it would be illogical to assume that Extell would proactively approach MTA in 2009 without an express indication from MTA that it might genuinely consider a proposal from Extell.

Let's take a look at the comparison chart produced by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn. DDDB says that Extell would have provided everything that Forest City Ratner would have.

Let's take a look at the comparison chart produced by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn. DDDB says that Extell would have provided everything that Forest City Ratner would have.I don't believe that's accurate; nor do I believe that the MTA's portrayal is fair, either.

MTA notes in legal papers that Extell had said it would "in all likelihood" receive up to $150 million in subsidy but did not indicate it had begun to negotiate with the city or state as FCR had.

In other words, Forest City Ratner had already locked in the subsidies. Indeed, a 2005 letter to the MTA from Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff indicated that the city would not offer similar subsidies to another plan.

Nor, said the MTA, did Extell offer indemnification for environmental risks and did not offer to pay MTA expenses in relocating the Vanderbilt Yard.

But the dismissal of the Extell bid leaves out a few things. (These are not all mentioned in the lawsuit.) FCR said it could address environmental risks by using Brownfield Tax Credits—presumably available to any developer. Extell, as noted, didn't have to build a temporary yard.

And it was never asked to develop its bid. In a cover letter, Extell's Barnett wrote, "We believe our proposal could have been even more detailed and responsive had the MTA offered a longer period for response to its RFP, either initially or in response to our formal written request for an extension. We regret that you declined our request."

Unlike FCR, Extell was not planning to build a new subway entrance--originally to cost $29 million, now $50 million--nor build a project that would add as large amount of new sales taxes. On the other hand, Extell wasn't asking for $305 million in direct subsidies from the city and state nor the gift of arena naming rights.

Bottom line

The bottom line is that no one ever did a full cost-benefit analysis for all the public parties on the Forest City Ratner deal or the Extell deal.

Another reasons for fuzziness

The petitioners pointed out another inconsistency:

Further, we note that MTA’s contention that the questionable valuation of FCR’s 2005 proposal at $379.4 million establishes that it actually got more than the $214.5 million value at which the Vanderbilt Yard was appraised is belied by the fact that MTA persuaded FCR to sweeten its proposal by adding $50 million in cash. According to MTA’s own valuations, FCR’s original proposal was already worth $329.4 million, which was around $95 million more than the value of Extell’s proposal, and around $115 [million] more than the appraised value of the Yard. Neither MTA nor FCR even attempts to explain why, if those valuations were accurate, FCR then agreed to increase its $50 million in cash to its proposal, purportedly increasing the proposal’s value to around $165 million more than the Yard’s appraised value.Note that the petitioners refer to $214.5 million as the appraised value; that should have been $271.2 million.

Public benefits

While the MTA claimed it did not need to follow a public bidding process, because the sale was allowed by the PAAA as furthering the public interest, there's no evidence, the suit charges, that the MTA conducted "any actual analysis of the public benefits to be gained by the sale of the Vanderbilt Yard to FCR," nor did it acknowledge the "diminishment of the Project’s anticipated public benefits."

The MTA and the FCR denied that.

The petition charged that, the MTA Board’s June 24, 2009 resolution merely recited, in rote fashion, the same “significant public uses and purpose” of the Project that it had recited in 2005, such as “the construction of thousands of rental housing units for low-, moderate- and middle-income New Yorkers”, “the erection of commercial office space to promote future economic growth and new jobs”, even though all or substantial portions of all of those benefits had already been either eliminated from the Project or put on indefinite hold.

The MTA and FCR denied that and referred the court to the resolution. However, while it offers other justifications for the deal, it does not acknowledge the doubts about the promised benefits.

DDDB's bid

The suit charges that the fair market value of the property was never discussed. It also charges that the MTA did not ask Extell for a competing proposal nor did it entertain DDDB's announced bid, at the June 24 meeting, of $120 million.

In an affidavit, former MTA board chair Dale Hemmerdinger called DDDB offer a political stunt rather than a bona fide responsive offer.

Also, the MTA said the UNITY Plan developed by DDDB failed to demonstrated the proposers' financial qualifications, no proven ability to obtain financing for projects of similar size. And it noted that the ESDC had previously rejected UNITY plan during its review of the project.

The petitioners responded:

While respondents seek to misrepresent DDDB’s proposal as a “sham” and a “publicity stunt”, neither of respondents claims to have made any genuine effort either to understand DDDB’s proposal or to determine whether it is viable, and MTA has simply precluded consideration of any proposal that might compete with its planned disposition of the Vanderbilt Yard to FCR.

...FCR asserts a similar argument that DDDB cannot be deemed a potential bidder because it could not have met the requirements stated in MTA’s 2005 RFP, which is both untrue and irrelevant. Like MTA, FCR does not explain why it would have made sense to submit a formal proposal in 2009 in response to MTA’s expired, four-year-old RFP, and does not contend that MTA would even have considered any such proposal.Public benefits

DDDB had (and still has) a viable, vetted plan for financing the development of the Vanderbilt Yard and could, if so required, could meet the funding and asset requirements of the RFP or another reasonable request for proposals.

Moreover, to the extent either FCR or MTA now pretends that MTA required strict compliance with the RFP in 2005, that position is undermined by MTA’s acceptance of FCR’s bid despite FCR’s unexplained failure (or refusal) to submit the 20-year pro forma profit-loss statement which the RFP expressly required as part of each proposal, and rejected Extell’s proposal which included the purportedly required profit-loss statement.

Did the MTA really analyze public benefits of the deal? In his affidavit, Hemmerdinger stated:

The Board determined, in addition, that the transaction would yield significant economic dividends to the residents of Brooklyn and those of the State as a whole.Except the board was drawing on conclusions by the ESDC, not more independent bodies like the Independent Budget Office (IBO), which called the arena a net money-loser for the city.

(The IBO's formal report came out after the MTA vote, but an IBO rep had testified to this effect at a state Senate oversight hearing in May.)

The MTA focused on construction jobs:

The Atlantic Yards Project is expected to greatly benefit the Brooklyn community. ESDC has estimated that it will generate over 10,000 new, direct job years and over 20,000 total job years, resulting in over $1 billion in total personal income.There's no reason to think that will specifically benefit Brooklyn.

FCR came up with different numbers:

The Project also will be a powerful engine of economic growth. ESDC estimates that construction of the Project will generate 16,427 new direct job years and 25,133 total job years (including direct, indirect and induced job years), resulting in $1.414 billion in total personal income (including direct, indirect and induced).Actually, according to the ESDC's 2009 Modified General Project Plan:

(i) Construction of the project will generate 12,568 new direct job years and 21,976 total job years (direct, indirect, and induced);Oddly, at another point in the legal papers, the MTA tried to change the subject:

(ii) Direct personal income related to construction activities will be $590.0 million and total personal income will be $1.2 billion (direct, indirect, and induced)

While Petitioners try to make much of changes to the Atlantic Yards Project as a whole since 2005, any such changes are irrelevant to the issue at hand, because they do not bear on the benefits to be received by MTA as a result of the disposal of Vanderbilt Yard.Smaller railyard OK

So why would a smaller railyard be OK? Because, said the MTA, its plans have changed:

Although FCRC's original design called for nine tracks and a capacity of 76 cars, the new design fully meets LIRR's future needs in view of a planned change in the use of the Upgrade Yards for reasons unrelated to this project. Specifically, once LIRR service into Grand Central Terminal begins, upon completion of LIRR's East Side Access project, LIRR will discontinue regularly scheduled service into Atlantic Terminal. Instead, LIRR will operate a shuttle service between Atlantic Terminal and Jamaica Station. Although LIRR will actually be running more frequent service once the switch to shuttle service is implemented, the Upgraded Yard will need to accommodate fewer and shorter trains.Depending on Ratner's bid

In his affidavit, Dellaverson further explained a reason to stick with the deal:

MTA was well aware that any project built on the Vanderbilt Yards property would require active involvement and funding by ESDC and new York City. It would have been virtually impossible to replace FCRC with any other bidder and still expect the project to move forward, and rebidding the project would also delay completion of the transit and yard improvements that the RFP had contemplated since 2005.Note that such improvements had not been contemplated before Forest City Ratner proposed the Atlantic Yards project.

Legal opinion obtained?

Did the MTA obtain a opinion from legal counsel advising it that its disposition of the Vanderbilt Yard was lawful? (I wrote that the MTA got a checkoff, at least.) In its answer, the MTA punted:

MTA declines to respond to the allegations… which concern privileged legal advice obtained by MTA.Compliance with PAAA

Both Forest City Ratner said the MTA complied with the PAAA because it had in the record the previous appraisal, from 2005.

Moreover, said FCR, the MTA board was not obligated to comply with the law, because a preliminary determination to dispose of the Vanderbilt Yard properties and development rights to FCR was made in 2005, before the effective date of the PAAA, and affirmed in 2006, with only “modifications to the business terms” approved in 2009.

The MTA, more cautiously, said “it arguably does not even apply.”

In an reply brief, the plaintiffs responded:

For one, respondents argue that the appraisal of the Vanderbilt Yard which MTA obtained in 2005 was still valid in 2009, even though MTA’s Chief Financial Officer publicly acknowledged on June 22, 2009, that the economy had substantially worsened and the real estate market in Brooklyn had substantially deteriorated since 2005, so as to warrant FCR’s withdrawal of its 2005 proposal and MTA’s negotiation of a new transaction with FCR.They don't explain how a new appraisal would've helped the MTA, but the point of the lawsuit is that the MTA evaded the law.

Deal "evolution"?

Was the 2009 transaction part of a sequence? The plaintiffs disagree:

Respondents also argue that the transaction which MTA’s Board approved on June 24, 2009, should be deemed to relate back to the proposal from FCR which MTA’s Board formally selected nearly four years earlier, on September 14, 2005, and which FCR subsequently withdrew. Thus, respondents contend that both transactions were really just part of an unprecedented four-year-long disposition of authority property, so that the MTA should be permitted to rely on the RFP which it issued and the appraisal of the Vanderbilt Yard which it obtained in 2005, before the PAAA was enacted, to meet the new procedural requirements of the PAAA in 2009.The plaintiffs pointed out that only FCR argues that the PAAA does not apply to the 2009 transaction--an argument “directly undermined by MTA’s own implicit admission” that it does apply, given an “explanatory statement” sent to designated State officials and legislators.

But that strained argument undermines the explicit remedial purpose of the PAAA, which is to reform the State’s public authorities by, among other things, “ensur[ing] greater efficiency, openness and accountability” in the disposition of authority property.

(Actually, the letter—at the end of the Helena Williams affidavit—says that transaction “may fall within the purview” of the PAAA.)

The issue of standing

The defendants say that the petitioners shouldn't even be in court.

The petitioners argued that DDDB, as a potential bidder, has been directly injured, and that it has organizational standing, given that the interests at issue "are sufficiently germane to the association's purposes that it is an appropriate representative of those interests."

So too the Straphangers has associational standing, given its interest in MTA operations, as do the elected officials represent districts encompassing or near the Vanderbilt Yard.

The suit said those officials--State Senator Velmanette Montgomery, Assemblymember Jim Brennan, Assemblymember Joan Millman--voted to pass the PAAA, "and are interested in ensuring that their votes are not rendered meaningless by MTA’s violation of the PAAA." (Also a plaintiff is City Council Member Letitia James.)

The MTA (as did FCR), however, responded none of the petitioners have standing, since the only injured party is another legitimate bidder--e.g., Extell--and DDDB wasn’t such a legitimate bidder.

The question of standing is one the petitioners hope the court will construe broadly, because “no party other than petitioners is in a position to challenge MTA’s unlawful action.”

Comments

Post a Comment